Overview

After more than a decade of working as a sustainability facilitator, I’ve come to recognize certain patterns that consistently show up in my practice. These patterns aren’t random—they reflect my character, personality, interests, and skills, many of which were shaped in my youth and early adulthood.

For those just starting out in this field, here’s something important: your facilitation style isn’t just a professional choice—it’s deeply personal. Understanding your own tendencies and strengths is a powerful first step in becoming the kind of practitioner who can create meaningful, lasting impact.

Where It All Began: The Value of Shared Purpose

My formal journey into building community around shared values began at Accenture, where I worked as a Learning Coach. I coordinated weeklong trainings for analysts, consultants, and managers across the Asia Pacific region. These large-scale sessions took place in the heart of Kuala Lumpur, blending logistical coordination with learning facilitation.

What stood out most during that time was the strength of the corporate culture—one rooted in shared values, ethics, and a collective sense of purpose. This alignment wasn’t just feel-good; it translated directly into business outcomes. Teams collaborated more efficiently, adapted faster in times of change, and made decisions with greater consistency and integrity. When people are aligned on values, they trust more deeply, take initiative with confidence, and commit to long-term goals—even under pressure. In a fast-paced consulting environment, that alignment became a competitive advantage.

I learned that when people operate from a shared value system, they move faster, trust more deeply, and make more resilient decisions.

This was a lesson I carried with me into community and sustainability work, where shared values are often less visible and harder to name. Yet the principle remains the same: lasting behavior change—whether it's recycling more, cycling to work, or reducing waste—rarely happens through information alone. People need to see their own values reflected in the action, feel connected to others doing the same, and believe that their effort contributes to something larger. As facilitators, part of our role is to help communities uncover and articulate those shared values. It’s a process that requires humility, empathy, and time—but it lays the foundation for collective action that sticks.

Navigating Complexity in Community Contexts

Communities are not teams in the traditional sense. They consist of people from different ages, genders, faiths, cultures, and educational backgrounds. And unlike the structured environment of corporate teams, communities often lack a shared language or unified goal.

As facilitators, we must create the conditions for common purpose to emerge. This means listening carefully, recognizing unspoken assumptions, and resisting the urge to lead with a predetermined agenda. It’s about meeting people where they are and working together to find alignment that feels honest and inclusive.

The Soft Skills That Make All the Difference

Too often, facilitation and communication are seen as secondary skills in sustainability work—extras that come after the "real" work is done. But the truth is, these soft skills are foundational. They shape how people feel in the process, and whether they trust you enough to engage meaningfully.

Good facilitation isn’t just about managing a meeting. It’s about building trust, enabling honest conversations, and helping people move from fragmented perspectives to shared understanding. Without that, even the best-designed solutions will struggle to take root.

Human-Centered Design: More Than a Toolset

One of the most transformative frameworks I’ve used is Human-Centered Design (HCD). At its heart, HCD is about empathy—it’s a way of understanding the needs, values, and lived experiences of a community within the context of place. This approach is particularly powerful when applied to mobility solutions, such as developing a community-driven cycling program for last-mile connectivity.

It's important to see HCD not just as a toolkit, but as a mindset. It requires you to observe deeply, listen actively, and validate insights through continued engagement.

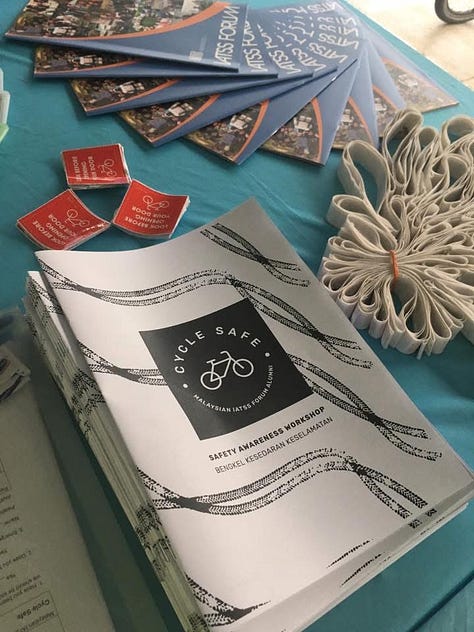

In 2018 my fellow IATSS Alumni members and Transition TTDI a community led sustainability collective in my neighborhood embarked on a project called Cycle Safe; a neighborhood campaign to encourage cycling, awareness of road sharing with cyclist, socializing bike sharing championed by the local council and integrating the MRT into our daily commute. The program design process started with my Alumni members identifying the stakeholders, resources and most importantly making the program immersive to identify the in the community’s transportation challenges/bias, defining key barriers, and brainstorming solutions that address real user needs—such as bike-sharing hubs, repair stations, and safe cycling routes. The program has different collaborators across the various phases from prototyping initiatives, testing with residents, and refining based on their feedback, the program evolves to become a meaningful, accessible mobility option.

Solutions that emerge from this process are more relevant, more inclusive, and more likely to be embraced—because they are co-created with the people they serve. As a resident and an alumni member, I was pleasantly surprised at the reach and support we gained throughout the process and beyond the implementation, it became a reference point for others who had heard about the program or seen the campaign. Whether designing for sustainability, accessibility, or urban mobility, Human-Centered Design ensures that every decision aligns with what matters most to the community.

This version seamlessly integrates the cycling program within the broader discussion of HCD, showing how the framework applies in a real-world sustainability initiative.

Stakeholder Mapping: The Groundwork of Impact

In any community initiative—like building edible gardens or launching recycling programs—may seem simple on the surface. But the journey from idea to implementation is rarely linear. It’s about learning how people interact with the place, each other, and the systems around them.

Stakeholder Identification: As an outsider to the community there are many individuals, working groups and systems at play in a place. For a deep and sustained program, I realized a slow introduction to the community is a great way to develop social credit.This includes spending time in shared spaces, attending local events, and talking informally with both primary and secondary stakeholders—from residents and domestic helpers to building maintenance teams, informal waste collectors, and NGOs.

From these observations and conversations, I begin to create tools like Behavior Maps and Knowledge Gap Analyses—visual guides that help clarify who does what, where values align, and what behaviors need support or change. These tools inform how we design the program, and who we invite to lead key parts of it.

Sometimes, we discover unexpected allies—residents who are passionate about the cause and eager to lead. Their involvement not only increases credibility, but also ensures the project continues long after the initial implementation.

Engaging Through Communication and Playful Design

Sustainability isn’t just about systems—it’s about people. And one of the most effective ways I’ve found to engage communities is through play-based learning.

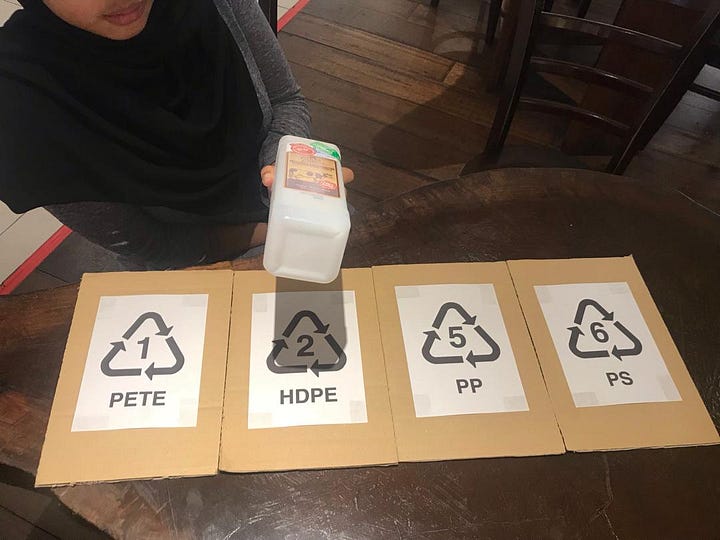

When our team began running waste separation workshops, we faced a common challenge: recyclers required plastics to be pre-sorted, but residents weren’t sure how. So we turned the process into a game—inviting participants to sort materials based on cleanliness and identification codes and offering prizes like guided tours of the Tzu Chi recycling center to keep things engaging.

For those who couldn’t attend, we shared short videos, fridge-friendly flyers, and tips through neighborhood WhatsApp and Facebook groups. These tools became touchpoints for continuous learning and even sparked spontaneous collaboration—like the time a young student collected two full bags of plastic bottle caps for a school mural, thanks to donations from neighbors responding to his call for help.

These efforts typically unfold over several months, requiring consistency, creativity, and cultural sensitivity. But when learning is joyful and accessible, behavior change becomes more likely—and more lasting.

Leveraging Community Leaders and Champions

Every project needs early adopters—the individuals who bring momentum, trust, and credibility to a new initiative. In community projects, these are often residents who participated during the exploration or pilot phase.

Support their leadership. Celebrate their efforts. As the project gains traction, these individuals often evolve into ambassadors, shaping how the wider community engages. In one project, for instance, a resident began collecting HDPE bottles for an NGO, linking a recycling initiative to educational access for underprivileged children. Another started a campaign to repurpose containers for feeding stray animals. When people connect personal values to collective action, the project becomes self-sustaining.

Final Thoughts: Designing for Equity, Inclusion, and Dignity

If there’s one thing I’ve learned, it’s this: sustainability work is about people—not just programs. As a facilitator, your role is to hold space for complexity, create moments of connection, and design processes that respect equity, dignity, and local wisdom.

Stay curious. Stay humble. Learn from the people you serve. Over time, your facilitation style will evolve—and so will your ability to build systems that support both people and the planet.

Let your practice be rooted in place, informed by the people it serves, driven by purpose, and alive with possibility.